Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta)

Click here for more detailed information.

Scientific Classification

Class: Reptilia

Order: Testuidae

Family: Cheloniidae

Genus: Caretta

Species: caretta

Species Description

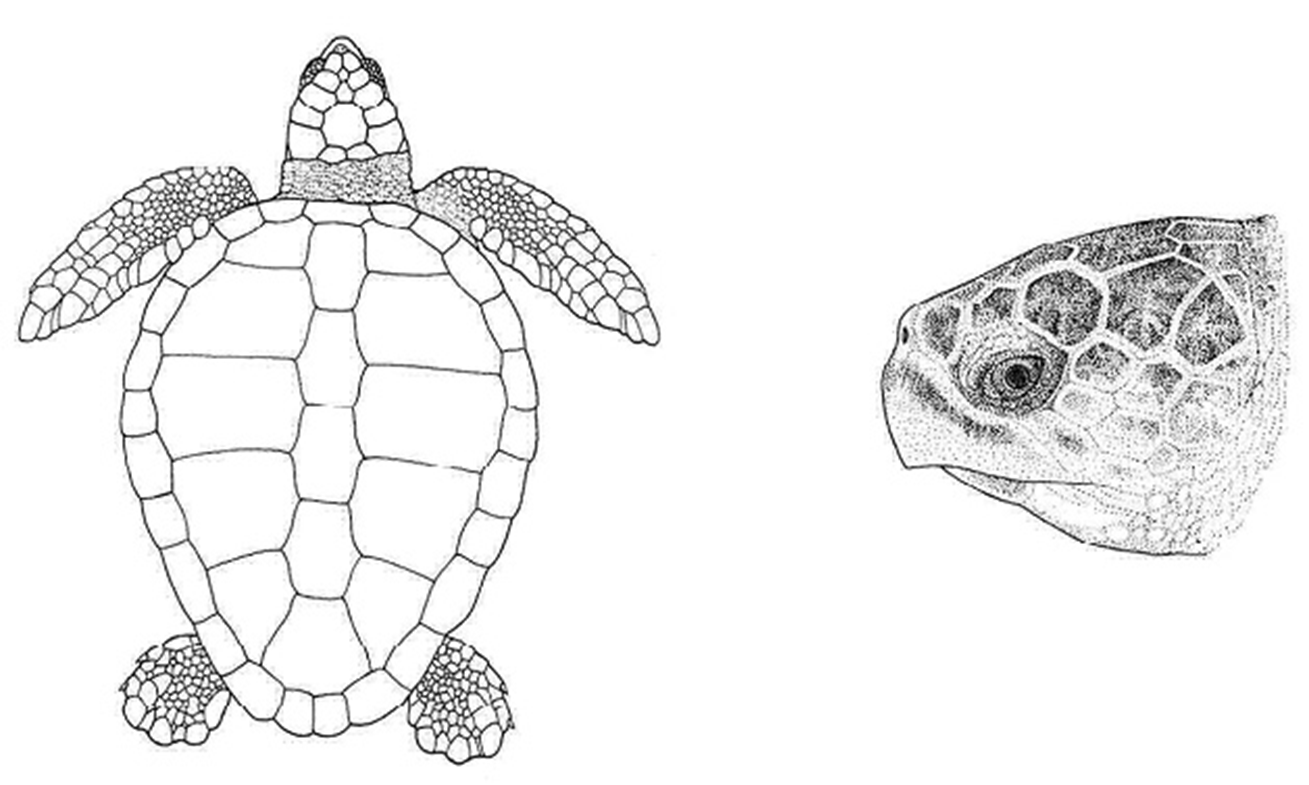

Large hard-shelled species of sea turtle

Carapace: Reddish-brown; Slightly heart shaped

Large, broad head

Typical Adult:

Weight: 170-350 lb (75-160 kg)

Length: 30-45 in (75-115 cm)

Conservation

Status

Threats

- Loss and disturbance of nesting habitat

- Interactions with fishing gear

- Pollution

- Lack of information

Natural History

Diet

Omnivore: squid, crabs, horseshoe crabs, jellyfish, sponges, coral, whelks, conch, algae and plants

Life History

Reproduction - Seasonal

Sexual maturity: 17-35 years

Breeding: Mid-March through June

Egg laying: April through September

Hatching: June through mid-November

Average clutch size: 120 eggs

Average clutches per season: 2-4

Range of nest incubation: 46-80 days

Lifespan

Unknown

- Do sea turtles cry? Many people have seen nesting females that look like they are crying. They are actually excreting excess salt. Sea turtles have salt glands near their eyes, which allow them to swallow seawater and excrete the salt in high concentrations.

- Do sea turtles need to breathe air? All sea turtles are reptiles and need to breathe air. They can hold their breath for long periods of time. Loggerhead dives usually last only 4 to 5 minutes, but they can actively dive for up to 20 minutes and can rest for hours without breathing.

- In the coldest months, loggerheads submerge for up to seven hours at a time, emerging for only seven minutes to breathe. These are among the longest recorded dives for any air-breathing marine vertebrate.

- Can sea turtles get too cold? Adults and juveniles in temperate waters migrate towards the equator for winter to avoid cold water. In water under 10ºC (50ºF), they can become “cold stunned.” When cold stunned, they become lethargic and float on the surface. If the water temperature drops below 5ºC (41ºF), the turtles could die.

- Aggression between females, which is uncommon in most marine vertebrates, is common among loggerheads. Aggression escalates from threat displays to combat. These fights primarily occur over access to feeding grounds.

- Inward-pointing, mucus-covered papillae found in the front of the loggerhead’s throat filter out foreign bodies, such as fishhooks, while holding on to jellyfish that the turtle has eaten.

Description

Loggerheads are large, hard-shelled sea turtles. They have huge heads and powerful jaws for feeding on shelled prey such as whelks and conchs. This sea turtle species is called a “loggerhead” because when resting at sea with just their heads out of the water, sailors often mistake them for floating logs.

They have a slightly heart-shaped carapace, which is often covered with commensal organisms such as barnacles and algae. It is estimated that up to 100 species may live on the carapaces of loggerhead turtles. This makes each turtle its own mobile ecosystem.

The carapace of adults is reddish-brown. The carapace of hatchlings is brown to dark gray. They also have a distinctive species-specific pattern to their scutes.

The skin of males is more brown and the head more yellow than those of females. Males also have wider carapaces and a long curved claw on each forelimb. Both males and females have two claws on each flipper.

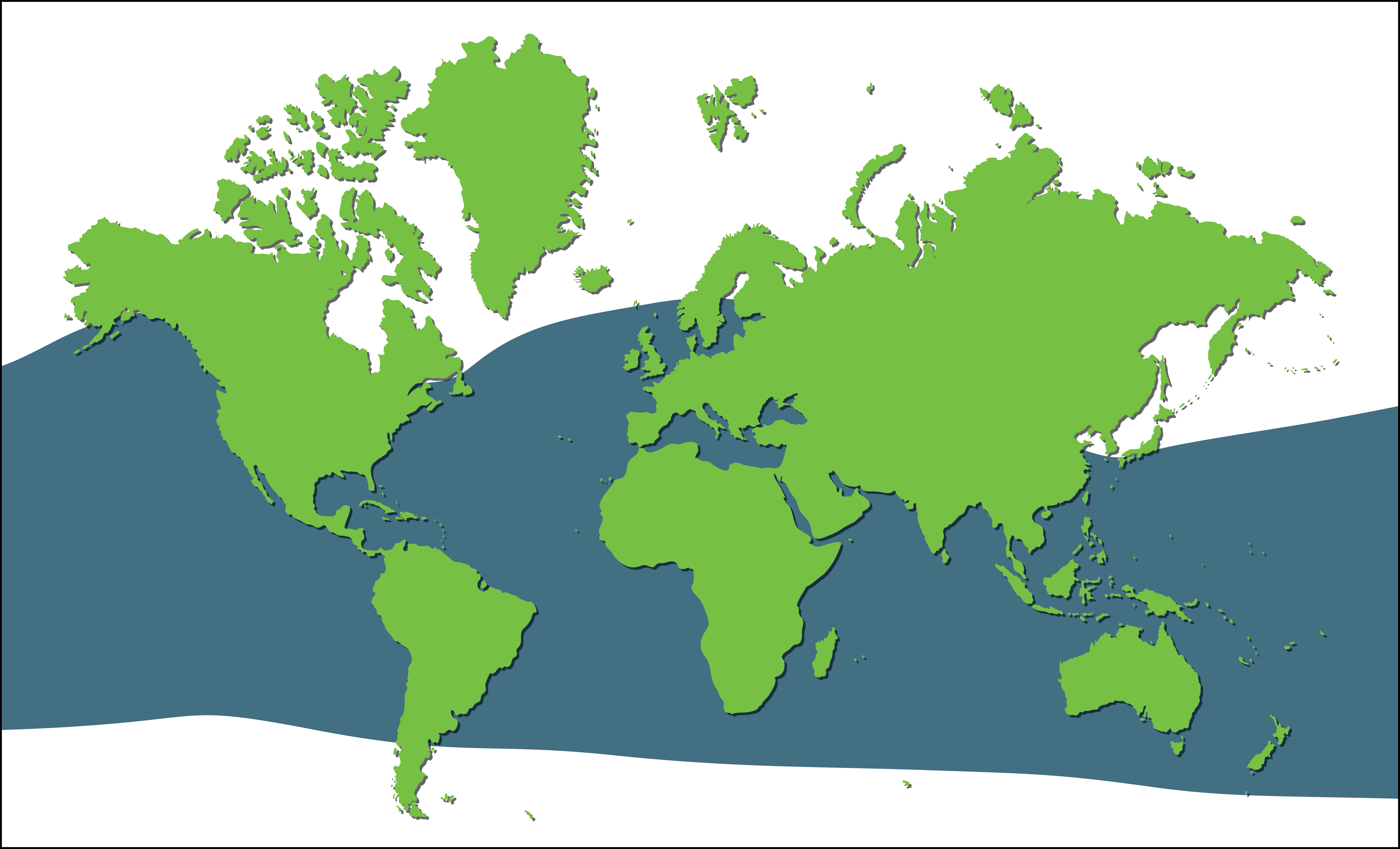

Distribution

The loggerhead sea turtle is found in more places around the world than any other species of sea turtle. They are found throughout both temperate and tropical waters. They are found along the continental shelves and river estuaries of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. They are also found in the Mediterranean Sea. The largest nesting area is along the southeast coast of the United States, from North Carolina to Florida.

Adult loggerheads are known to make long migrations between feeding areas and nesting beaches. When not nesting, adult females born on U.S. beaches are distributed in waters off the eastern U.S. and throughout the Gulf of Mexico, Bahamas, Greater Antilles and Yucatán.

Habitat

Loggerheads occupy three different ecosystems during their lives:

- Sandy beaches

- Open ocean

- Nearshore coastal areas

Loggerheads nest on ocean beaches, generally preferring high energy, relatively narrow, steeply sloped and coarse-grained beaches.

Diet

Loggerhead turtles are omnivores, eating both plants and animals. They mostly eat animals. They use their massive and powerful jaws to break open the hard shells of such prey as whelks and conchs. They also eat many other invertebrates such as jellyfish, shrimp, sea urchins, octopus and squid.

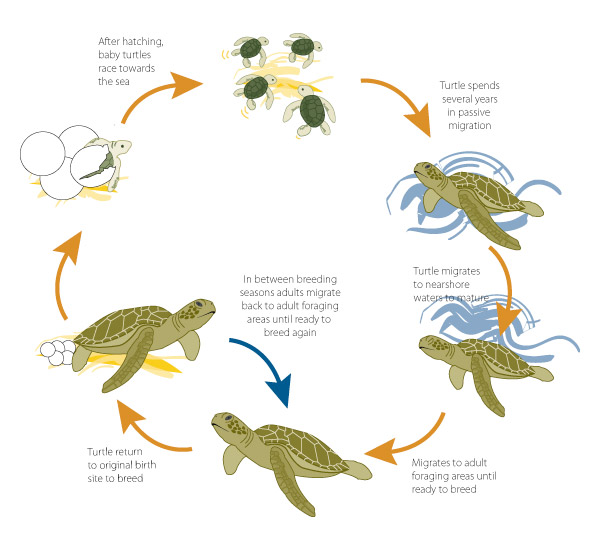

Life History

Loggerheads spend most of their lives in the open ocean or in shallow coastal waters. They almost never come ashore. Adult females only come ashore to nest. Males usually don’t come ashore at all. Adults tend to return to the same nesting grounds year after year and many females return to the very beach where they themselves hatched.

As breeding season approaches, turtles migrate from their feeding areas to mating areas that are located just offshore of the nesting beaches. Loggerheads have some of the longest migration routes of any sea turtle. Pacific loggerheads migrate over 7,500 miles (12,000 km) between nesting beaches in Japan and feeding grounds off the coast of Mexico.

The males arrive first. Courtship and mating begin once the females arrive. Mating occurs from mid-March through early June each year. In Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina nesting begins in May and ends in August. Most adult males return to the feeding grounds in mid-June. The females remain until they finish nesting on the nearby beaches.

Female loggerheads nest only every two to three years. They usually crawl onto the beaches and nest at night. The turtles dig an egg chamber with their back flippers, deposit eggs, cover the nest with sand and return to the ocean. This process takes about one to two hours.

Each female usually lays between one and seven clutches of eggs during a nesting season. There are approximately 14 days between clutches. Between clutches, they return to the sea and mate. The clutch size averages between 100-125 eggs. After the female has produced her last nest, she too leaves and begins the long journey back to her feeding grounds.

Sometimes you don’t actually have to see the turtle to know which species has been on a beach. When nesting females come onto a beach, they leave tracks, or “crawls”, made by their front flippers. These “crawls” are distinctive for each species.

The eggs incubate from 53 to 80 days and (if left alone) up to 75% of the eggs laid successfully hatch. Environmental temperature is very important to developing eggs. How fast the egg develops (length of incubation) depends on the temperature within the nest. This temperature can be affected by sun, shade, rain, heat generated within the nest and an egg’s position in the nest. At cool temperatures, around 25ºC (77ºF), incubation can last 65 to 80 days. At warmer temperatures, around 35ºC (95ºF), incubation lasts for 45 to 60 days. Eggs incubated at too cold or too hot a temperature will not hatch.

The sex of the turtle is also determined by the temperature of the nest during the middle third of incubation (this is called temperature dependent sex determination, or TSD).

Loggerheads usually hatch at night. Immediately after hatching, the hatchlings dig through the sand surrounding the nest towards the surface. Once on the surface, the hatchlings quickly orient and move towards the ocean using moonlight on the water as a guide. Once in the water, the hatchlings swim for about 20 hours. This takes them about 14-17 mi (22-28 km) offshore. At this point, they hide in sargassum rafts or debris. Upon reaching about 18 in (45 cm) in length, they migrate to near shore and river estuaries of the eastern United States, the Gulf of Mexico and the Bahamas.

Threats

Sea turtles face threats both on nesting beaches, in their feeding grounds and in the open ocean. The greatest causes of population decline and the primary threats to loggerheads worldwide are long-term harvest by people and incidental capture in fishing gear.

Sea turtles face different predators as they age.

Eggs and hatchlings are the most vulnerable. They may be eaten by a wide range of coastal predators, such as crabs, large lizards, small mammals (e.g. raccoons, coatis, dogs, coyotes, etc.) and a variety of birds of prey and shorebirds. They are also threatened by many types of insects and worms. The most destructive nest predator in the United States is the raccoon.

Young loggerhead sea turtles can be eaten by cephalopods, sharks and other large fish once they are in the ocean.

Adults face fewer serious predators, although large marine predators such as sharks, seals and orcas will occasionally attack adult sea turtles. Nesting females are attacked by flies, feral dogs and humans.

Hunting. Loggerhead sea turtles were once intensively hunted for their meat and eggs. Laws and education efforts all over the world have decreased the number of turtles being eaten by humans. Unfortunately, turtle meat and eggs are still consumed in countries where laws are not strictly enforced.

Commercial Fishing. Where turtle foraging habitat and commercial fishing occur together, bycatch is very high. The commercial fishery that accidentally kills the most loggerheads is bottom trawling to catch shrimp in the Gulf of California. Unattended fishing gear is also a problem, especially in the open ocean. Turtles often become entangled in longlines or gillnets. They also become stuck in traps, pots and dredges. Turtle excluder devices (TEDs) for nets and other traps have helped reduce the number of sea turtles being accidentally caught.

Pollution:

Trash. Turtles eat a wide array of the 24,000 metric tons of floating trash dumped in the ocean each year. This includes such items as bags, sheets, pellets, balloons and abandoned fishing line. Loggerheads may mistake the floating plastic for jellyfish, a common food item. When turtles eat plastic, it causes many health concerns, including blocked intestines, malnutrition, suffocation, ulcers and starvation. Ingested plastics also release toxins that accumulate in the turtle’s tissues. Such toxins lead to thinner eggshells, tissue damage and unusual behavior.

Artificial lighting. Artificial light impacts nesting females and hatchlings. Females seem to prefer nesting on beaches free of artificial lighting. Loggerhead hatchlings automatically move towards the ocean using reflected moonlight or starlight on the water as a guide. Artificial light is brighter and can confuse them so they navigate inland towards that light and away from the ocean. Artificial lighting causes tens of thousands of hatchling deaths per year.

Climate Change. Changes in global temperatures can affect the turtles in many ways. Since the sex of turtle hatchlings depends on the temperature in which they are incubated, high sand temperatures may change sex ratios and result in more females. In fact, nesting sites exposed to unusually warm temperatures over a three-year period produced 87–99% females. This raises concern that global temperature changes may result in too few males to sustain the population. Also, climate change will cause water levels to rise degrading or destroying nesting beaches. Click here for more information on the impact of climate change on sea turtle populations.

Habitat Destruction. Habitat destruction and intrusion on the habitat by humans is serious threat to loggerhead sea turtles. The best nesting beaches for this species are open with broad sandy beaches above the high-tide line. Unfortunately, these are also the best recreational beaches. Beach development for people deprives the turtles of suitable nesting areas, forcing them to leave or nest closer to the water.

Growth of cities often leads to the siltation of sandy beaches and the construction of docks and marinas can destroy near-shore habitats. Boat traffic and dredging damages habitat and can also injure or kill turtles when boats collide with turtles at or near the surface.

Our lack of knowledge about the population and life history of loggerhead sea turtles makes it very difficult to understand what this species needs to survive and thrive.

Conservation

The loggerhead turtle is considered endangered by the IUCN and international trade in loggerhead turtle body parts is prohibited by CITES. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also list the loggerhead as a threatened species throughout its range in the U.S. Globally, the species continues to suffer an overall decline. The conservation and recovery of the loggerhead turtle requires international cooperation in order to address all of the threats to this species.

In the U.S., National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) protect sea turtles. NOAA monitors the turtles while they are in the ocean and USFWS while they are on the nesting beaches. Federal and state agencies have developed regulations to eliminate or reduce threats to sea turtles. For example, in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, NOAA requires measures to reduce sea turtle bycatch. NOAA works closely with the shrimp trawl fishing industry to develop turtle excluder devices (TEDs) to reduce the number of sea turtles accidentally captured in shrimp trawl gear. TEDs that exclude even the largest sea turtles are now required in shrimp trawl nets. Since 1989, the U.S. has prohibited the importation of shrimp harvested in a manner that negatively impacts sea turtles.

Sea turtle conservation is not just the responsibility of the government. We can help too. In many places during the nesting season, scientists, workers and volunteers search the coastline for nests. They may, if necessary, relocate the nests for protection from disturbance and threats, such as high spring tides or predators. After the eggs hatch, volunteers help scientists uncover and tally hatched eggs, undeveloped eggs and dead hatchlings. Any remaining live hatchlings are released or taken to research facilities. Researchers also look for nesting females for tagging studies and may gather barnacles and tissues samples from the females.

Ways we can help:

- Limit our use of plastics

- Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle (see Womble’s Tale)

- Use only turtle friendly products

- Respect sea turtles beaches and nests

- Support sea turtle research

- Volunteer with a recommended sea turtle conservation organization

- Support your local sea turtle conservation organizations

Bowen, B.W.; Abreu-Grobois, F.A.; Balazs, G.H.; Kamezaki, N; Limpus, C.J.; Ferl, R.J. (1995). Trans-Pacific migrations of the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) demonstrated with mitochondrial DNA markers”(PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 (9): 3731–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.9.3731. PMC 42035. PMID 7731974.

Conant, Therese A.; Peter H. Dutton, Tomoharu Eguchi, Sheryan P. Epperly, Christina C. Fahy, Matthew H. Godfrey, Sandra L. MacPherson, Earl E. Possardt, Barbara A. Schroeder, Jeffrey A. Seminoff, Melissa L. Snover, Carrie M. Upite, and Blair E. Witherington (2009). Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta) 2009 Status Review Under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (PDF). Loggerhead Biological Review Team.

Dodd, Kenneth (1988). “Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Loggerhead Sea Turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus 1758)” (PDF). Biological Report 88 (14) (FAO Synopsis NMFS-149, United States Fish and Wildlife Service): 1–83.

Ernst, C. H.; Lovich, J.E. (2009). Turtles of the United States and Canada (2 ed.). JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9121-2.

Janzen, Fredric J (1994). “Climate change and temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles” (PDF). Population Biology 91 (16): 7487–7490.

Lorne, Jacquelyn; Michael Salmon (2007). “Effects of exposure to artificial lighting on orientation of hatchling sea turtles on the beach and in the ocean” (PDF). Endangered Species Research 3: 23. doi:10.3354/esr003023.

Miller, Jeffrey D.; Limpus, Collin J.; Godfrey, Matthew H. (2003). “Nest site selection, oviposition, eggs, development, hatching and emergence of loggerhead turtles”. In Bolten, A., Witherington, B. Loggerhead Turtles. Smithsonian Books. pp. 125–143. ISBN 1588341364.

National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1998). Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta) (PDF). Silver Spring, MD.: National Marine Fisheries Service. Archived from the original on 2010-10-25. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

Spotila, James R. (2004). Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press and Oakwood Arts. ISBN 0-8018-8007-6.

US Fish and WIldlife Service, North Florida Ecological Services, Loggerhead Turtle Fact Sheet.

Witherington, Blair (2006). “Ancient Origins”. Sea Turtles – An Extraordinary Natural History of Some Uncommon Turtles. St Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7603-2644-4.

Yntema, C.; N. Mrosovsky (1982). “Critical periods and pivotal temperatures for sexual differentiation in loggerhead sea turtles”. Canadian Journal of Zoology 60 (5): 1012–1016. doi:10.1139/z82-141. ISSN 1480-3283.