Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas)

Click here for more detailed information.

Scientific Classification

Class: Reptilia

Order: Testuidae

Family: Cheloniidae

Genus: Chelonia

Species: mydas

Species Description

Large hard-shelled species of sea turtle

Carapace: Heart shaped and smooth, with shades of black, gray, green, brown, and yellow

Typical Adult:

Weight: 300-350 lb (135-160 kg)

Length: 36 in (91 cm)

Conservation

Status

Threats

- Hunting

- Interaction with fishing gear

- Habitat destruction

- Disease

- Pollution

- Climate change

- Lack of information

Natural History

Range

Tropical and subtropical waters throughout the world

Habitat

Open ocean (Pelagic)

Open sandy beaches for nesting

Shallower waters of reefs, bays and protected shores with sea grass beds or coral reefs

Diet

Herbivore: mainly sea grass and algae

Life History

Reproduction - Seasonal

Sexual maturity: between 10 and 50 years

Breeding: June to September

Average clutch size: 135 eggs

Average clutches per season: 3 (up to 7)

Renesting interval: 14 days

Range of nest incubation: 60-75 days

Lifespan

Unknown

- Green sea turtles have green fat. This is where they get their name (not from the color of their shell, as many people think).

- Unlike other turtles who only come on land to nest, green sea turtles can sometimes be found basking on beaches.

- Green sea turtles can hold their breath longer than any other sea turtle, sometimes for more than three hours!

Description

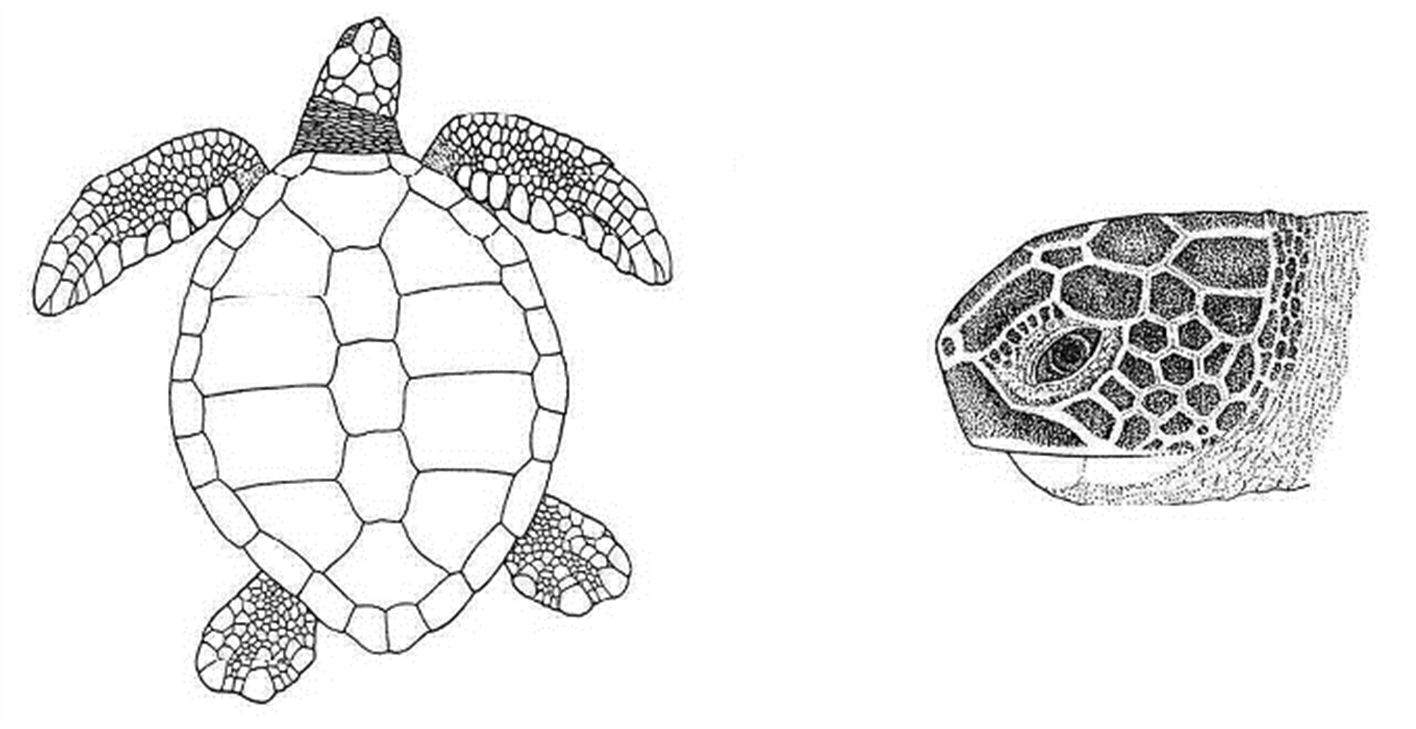

The green sea turtle is the largest of the hard-shelled sea turtles. The carapace is smooth and heart-shaped. The color of the carapace varies and has shades of black, gray, green, brown, and yellow. The plastron is yellowish white. The head appears small when compared to the body.

Greens have a single claw on each flipper. They have a distinctive pattern of scales and scutes as well. Their body fat is green.

Hatchlings have a black carapace, white plastron and white edging on the shell and limbs.

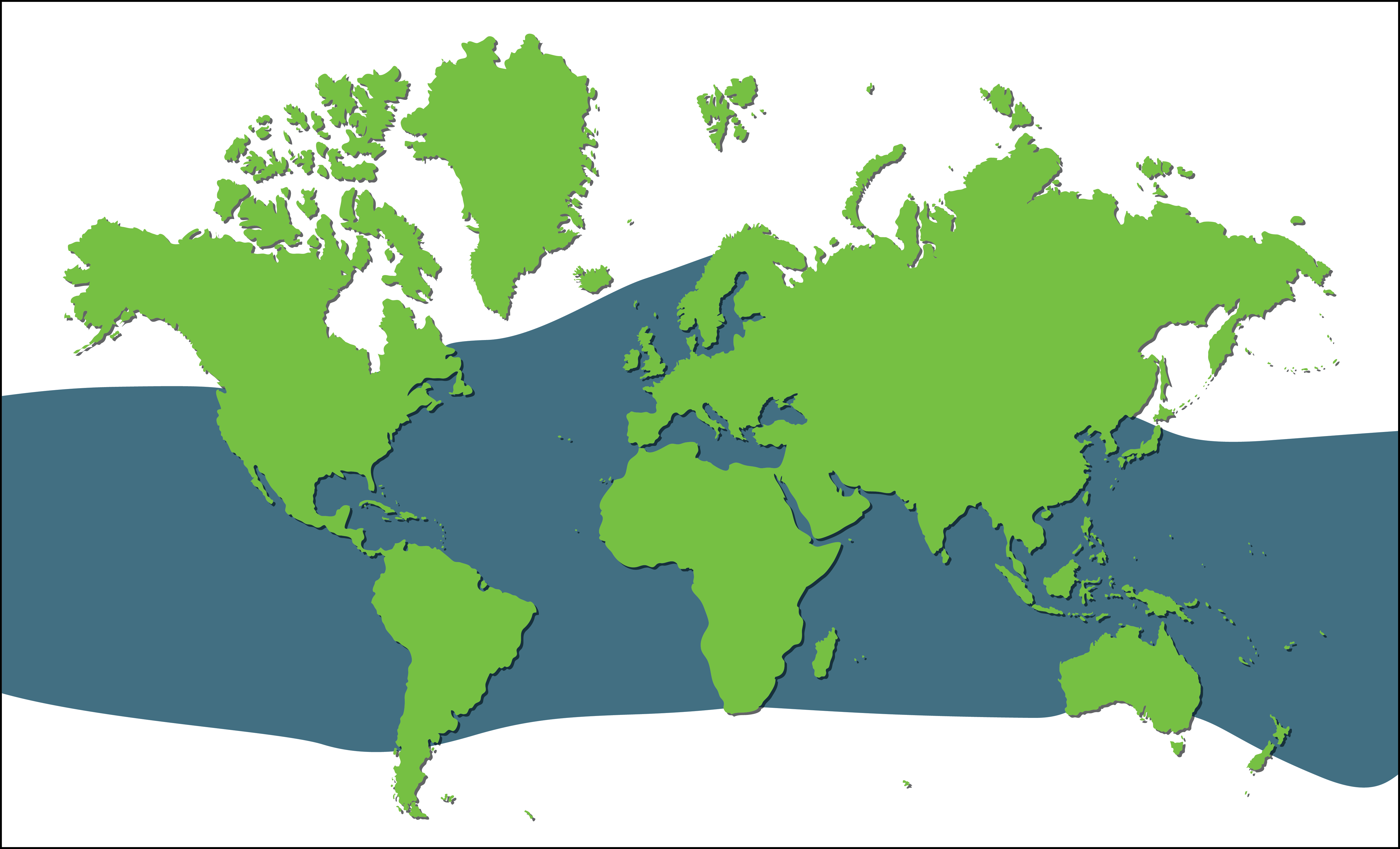

Distribution

Green sea turtles are found in tropical and subtropical waters throughout the world. They live in the coastal areas of more than 140 countries and nest on the beaches of over 80 countries.

In the United States, green sea turtles are found in near-shore waters along the gulf coast and Atlantic coasts as far north as Massachusetts. They are also found in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico. There are many important feeding areas in Florida. Along the Pacific coast, green sea turtles have been sighted from Baja California to southern Alaska. In the central Pacific, green turtles occur around most tropical islands, including the Hawaiian Islands.

Green sea turtles will migrate long distances between feeding grounds and nesting beaches.

Habitat

Green sea turtles use three different habitats depending on their age:

- Sandy beaches

- Open ocean

- Reefs, bays, protected inlets

Greens mature, feed and nest in very different areas. As hatchlings and youngsters, they are found in open oceans associated with sargassum rafts. When they reach 20 to 25 cm (8 to 10 inches) in length, they leave these rafts and move to feeding grounds. These feeding grounds are found in the relatively shallower waters of reefs, bays and protected inlets. They prefer open beaches with a sloping approach for nesting. As they move between feeding grounds and nesting beaches, they spend time in the open ocean.

Diet

When young, green sea turtles eat a variety of plants and small animals (omnivorous) found in and around the sargassum rafts. As adults, they eat mainly sea grass and algae (herbivorous). It is believed that the green color of their fat is a result of this diet.

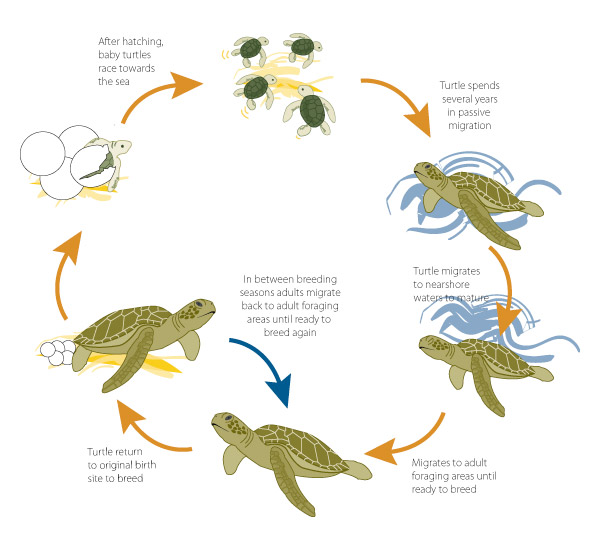

Life History

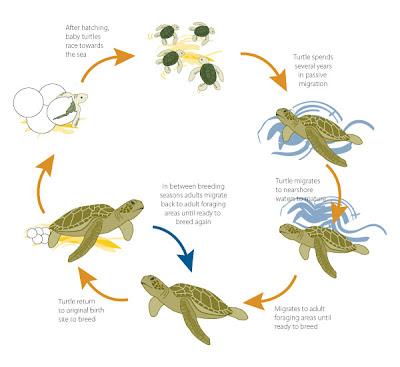

Green sea turtles, like all sea turtles, spend most of their lives in the water. In general, once sea turtles enter the water, they never come back on land except to nest. However, the green sea turtle occasionally comes ashore to bask.

With many reptiles, size is a more reliable indicator of sexual maturity than age. This is the case with sea turtles. It is estimated that male and female green sea turtles become large enough to be sexually mature between 20 and 50 years of age. When ready to breed, males and females migrate from their foraging areas to waters just off shore from the nesting beaches. Mating occurs in these waters. The breeding season is from June to September.

Females are known to nest on the same beaches on which they were born. They often travel thousands of miles between feeding and nesting areas.

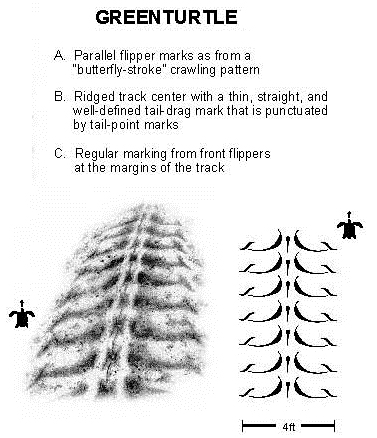

Individual females usually nest only once every two to four years. When a female is ready to lay eggs, she crawls onto the beach – usually at night. She crawls until she is above the high tide line. She then digs a deep nest with her rear flippers. She deposits up to 200 eggs into the nest. When finished laying eggs, she covers the clutch with sand, disturbs the general area and returns to the ocean. She leaves behind a distinctive crawl pattern. The egg laying process takes an average of two hours.

She may repeat this process every 12 to 14 days until she has laid as many as seven separate clutches (usually three to four). When she is finished laying all of her eggs she returns to the sea to begin the long journey back to her feeding grounds.

Incubation lasts from 45 to 75 days. Like most reptiles, the temperature at which an egg is incubated determines its sex. This is referred to as temperature dependent sex determination, or TSD. Hatching rates of undisturbed nests are usually high.

Hatchlings usually emerge from the nest at night. After the little hatchlings dig their way out of the nest, they quickly orient and move towards the ocean. They use moonlight and starlight reflected from the surface of the water as a guide. Once in the ocean, they swim for a long time without stopping. It is thought that they find beds or rafts of sargassum algae to float around with. It is there that they begin to eat and grow.

Threats

Sea turtles face threats on nesting beaches, in their feeding grounds and in the open ocean. The greatest causes of population decline and the primary threats to greens worldwide are long-term harvest by people and incidental capture in fishing gear.

Sea turtles face different predators as they age.

Eggs and hatchlings are the most vulnerable. They may be eaten by a wide range of coastal predators, such as crabs, large lizards, small mammals (e.g. raccoons, coatis, dogs, coyotes, etc.) and a variety of birds of prey and shorebirds. They are also threatened by many types of insects and worms. The most destructive nest predator in the United States is the raccoon.

Young greens sea turtles can be eaten by cephalopods, sharks and other large fish once they are in the ocean.

Adults face fewer serious predators, although large marine predators such as sharks, seals and orcas will occasionally attack adult sea turtles. Nesting females are attacked by flies, feral dogs and humans.

Hunting. Historically, the principal cause of decline in the green sea turtle population was long-term harvest. Eggs and adult females were harvested on nesting beaches. Juveniles and adults were harvested on feeding grounds. Although this practice is much less common now, it still occurs in many areas around the world.

Commercial Fishing. Accidental capture in fishing gear is a serious ongoing cause of death that also negatively affects the population.

Pollution:

Trash. Turtles eat a wide array of the 24,000 metric tons of floating trash dumped in the ocean each year. This includes such items as bags, sheets, pellets, balloons and abandoned fishing line. When turtles eat plastic, it causes many health concerns, including blocked intestines, malnutrition, suffocation, ulcers and starvation. Ingested plastics also release toxins that accumulate in the turtles tissues. These toxins lead to thinner eggshells, tissue damage and unusual behavior.

Artificial lighting. Artificial light impacts nesting females and hatchlings. Females seem to prefer nesting on beaches free of artificial lighting. Hatchlings automatically move towards the ocean using reflected moonlight or starlight on the water as a guide. Artificial light is brighter and can confuse them so they navigate towards that light and away from the ocean. Artificial lighting causes tens of thousands of hatchling deaths per year.

Climate Change. Changes in global temperatures can affect the turtles in many ways.

- Since the sex of sea turtle hatchlings depends on the temperature at which the eggs were incubated, high sand temperatures may change sex ratios resulting in too few males to sustain the population.

- As water levels rise, a number of good nesting beaches will be lost.

- The areas where sea turtles feed may be dramatically altered by climate change.

Click here for more information on the impact of climate change on sea turtle populations.

Habitat Destruction. Habitat destruction and intrusion on the habitat by humans is a serious threat to sea turtles worldwide. Beach development for people deprives the turtles of good nesting areas, forcing them to leave or nest closer to the water.

Growth of cities often leads to the siltation of sandy beaches and the construction of docks and marinas can destroy near-shore habitats. Boat traffic and dredging damages habitat and can also injure or kill turtles.

Our lack of knowledge about the population and life history of green sea turtles makes it very difficult to understand what this species needs to survive and thrive.

Conservation

All over the world sea turtle populations continue to decline. Their conservation and recovery requires international cooperation in order to address all of the threats to these species. The green sea turtle is considered to be endangered throughout its range.

In the U.S., the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) protect sea turtles. NOAA monitors the turtles while they are in the ocean and USFWS while they are on land. Federal and state agencies have developed regulations to eliminate or reduce threats to sea turtles. For example, NOAA works closely with the shrimp trawl fishing industry to develop turtle excluder devices (TEDs) and reduce the death of sea turtles accidentally caught in shrimp trawl gear. TEDs that are large enough to exclude even the largest sea turtles are now required in shrimp trawl nets. The USFWS, in partnership with other organizations, provides protection for sea turtles and their nests during the nesting season.

You can help too. In many places, workers and volunteers from many different organizations help protect the turtles during the nesting season. Volunteers help locate and protect nests, relocate nests that are threatened by disturbance or guide hatchlings to the ocean. Even after the eggs hatch, these volunteers can assist scientists as they uncover and count the eggs and hatchlings left in the nest.

There are many other ways that we can help as well:

- Limit our use of plastics

- Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle (see Womble’s Tale)

- Use only turtle friendly products

- Respect sea turtles beaches and nests

- Support sea turtle research

- Volunteer with a recommended sea turtle conservation organization

- Support your local sea turtle conservation organizations

Ernst, C., J. Lovich, R. Barbour. 1994. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Sea Turtle Conservancy. Species Fact Sheet: Green Sea Turtle (Online). Accessed March 30, 2012.

Spotila, James R. (2004). Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press and Oakwood Arts. ISBN 0-8018-8007-6.

US Fish and WIldlife Service, North Florida Ecological Services, General Sea Turtle Information.