Flatback Sea Turtle (Natador depressus)

Click here for more detailed information.

Scientific Classification

Class: Reptilia

Order: Testuidae

Family: Cheloniidae

Genus: Natador

Species: depressus

Species Description

Medium-sized sea turtle

Carapace: Smooth; Grayish; Upturned edges

Flat body

Typical Adult:

Weight: 200 lb (90 kg)

Length: 39 in (100 cm)

Conservation

Status

Threats

- Habitat loss and degradation

- Wildlife trade

- Hunting

- Accidental capture in fishing gear

- Climate Change

- Pollution

- Lack of information

Natural History

Diet

Carnivore: primarily invertebrates like sea cucumbers, jellyfish, shrimp and mollusks. Will occasionally eat seaweed.

Life History

Reproduction - Seasonal

Sexual maturity: 10-50 years

Breeding: varies by location,

some populations not seasonal

Average clutch size: 50 eggs

Average clutches per season: 2-3

Renesting interval: 15 days

Range of nest incubation: 55-60 days

Lifespan

Unknown

- For a long time, flatbacks were thought to be a type of green turtle. They were finally described as a separate species in 1988.

- Flatbacks have the largest eggs and hatchlings relative to their adult body size of all sea turtles.

- Flatbacks have a unique physiology that allows them to stay active underwater for longer periods than most other species.

- Over much of their nesting range, they are hunted by saltwater crocodiles. Because saltwater crocodiles also attack people, there are almost no underwater photos of adults taken in the wild.

Description

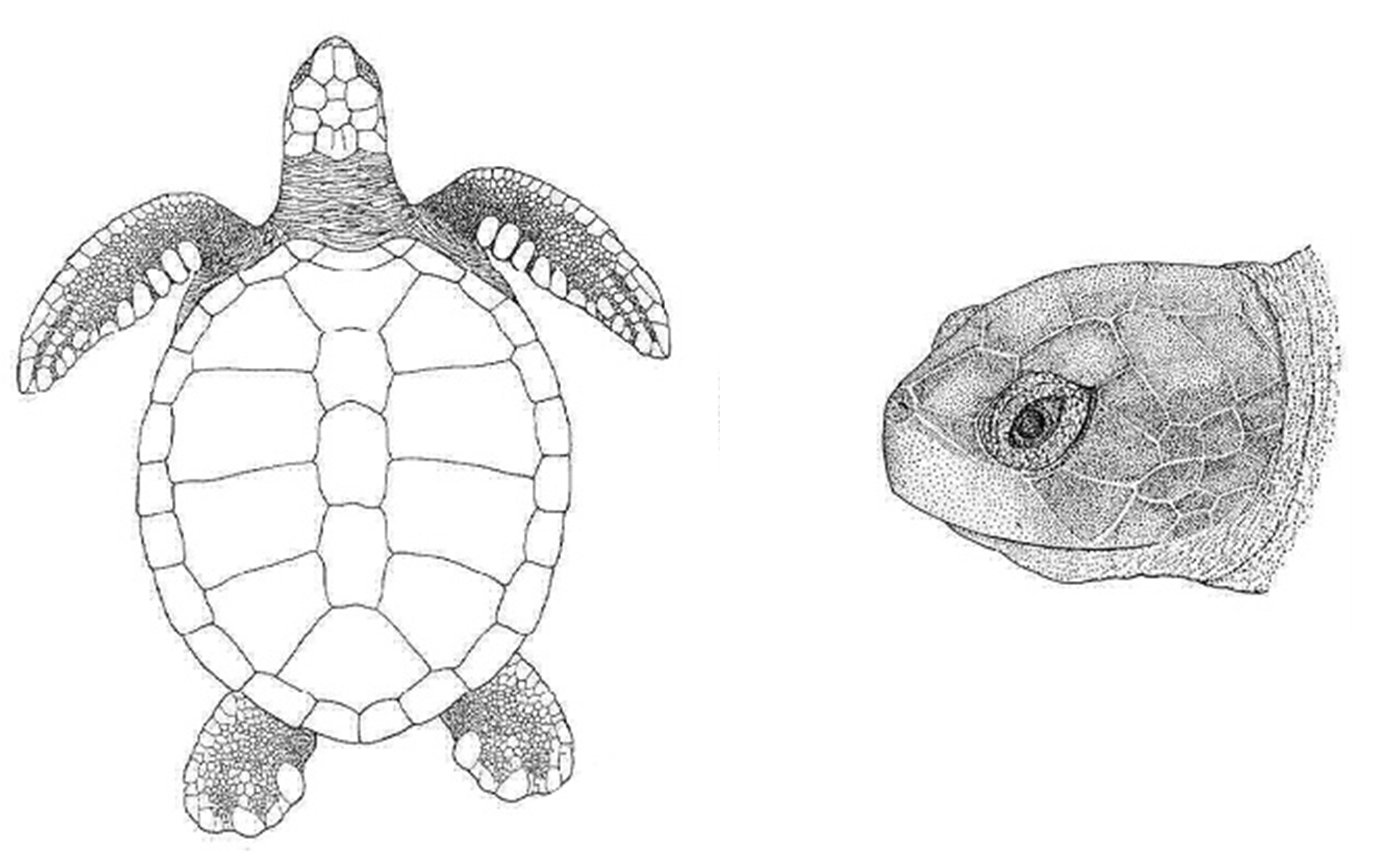

The flatback is a medium-sized hard-shelled sea turtle. The body is flat. The carapace has a thin, oval shape, with large non-overlapping scutes. The carapace is olive gray with brown/yellow margins. The carapace is turned up at the edges. The plastron is pale yellow. The head and front flippers are gray. Each flipper has one claw.

Distribution

Flatback sea turtles are unique because they live their entire lives on the continental shelf north of the Australian continent. They never spend time in the open ocean. Beaches on small offshore islands are their most important nesting sites.

Habitat

Flatback sea turtles live all their life stages in the same location and habitat.

- Gently sloping, sandy beaches with broad intertidal platforms

- Coastal waters and bays

These turtles prefer shallow, soft-bottomed seabed habitats that are far from reefs. They rarely leave the shallow waters of the continental shelf and nest only in northern Australia. Flatback sea turtles are found in coastal waters. They are reported to spend long periods of time floating on the surface of the water basking in the sun.

Diet

The flatback turtle is mainly carnivorous, feeding on squid, sea cucumbers, soft corals and mollusks. Occasionally they will eat seaweed.

Life History

Flatback sea turtles, like all sea turtles, spend most of their lives in the water. In general, once sea turtles enter the water they never come back on land except to nest. Unlike other sea turtle species, this one never spends time in the open ocean.

With many reptiles, size is a more reliable indicator of sexual maturity than age. This is the case with sea turtles. For example, it is thought that the flatback reaches sexual maturity sooner than the other species of sea turtle because their high-protein diet contributes to rapid growth.

The nesting season varies by location. It runs from October to February in Queensland’s Northern Territory, but may occur year round in northwestern Australia.

The females usually nest at night. When a female is ready to lay eggs, she crawls up on the beach. Most nests are dug on top of dunes or as high as possible on the beach. She digs the egg chamber with her back flippers. Flatbacks can nest up to four times in a season. The interval between each nesting is usually 15 days. An average of 50 eggs are laid in each clutch. The flatback lays larger eggs than the other sea turtle species.

Incubation lasts from 45 to 75 days. Like most reptiles, the temperature at which an egg is incubated determines its sex. This is referred to as temperature dependent sex determination, or TSD.

Hatchlings usually emerge from the nest at night. After the little hatchlings dig their way out of the nest, they quickly orient and move towards the ocean. They use moonlight and starlight reflected from the surface of the water as a guide. Unlike other sea turtle hatchlings, these turtles do not swim out into the open ocean. They spend their entire lives in the shallow waters of the continental shelf.

Threats

Flatback sea turtles face threats on nesting beaches and in their feeding areas. The greatest causes of population decline and the primary threats to flatbacks are are long-term harvest by people and incidental capture in fishing gear.

Sea turtles face different predators as they age.

Eggs and hatchlings are the most vulnerable. They may be eaten by a wide range of coastal predators, such as crabs, large lizards, small mammals and a variety of birds of shore birds and birds of prey.

Juveniles and adults face fewer serious predators, although large marine predators such as saltwater crocodiles occasionally attack and eat them.

Nesting females are also attacked or harassed by feral dogs, large predators, biting flies and humans.

A disease called fibropapillomatosis (FP), which is frequently reported in green turtles, has also been reported in flatback turtles. Its impact on the population is unknown.

Hunting. Historically, the principal cause of decline in sea turtles populations worldwide was long-term harvest. Eggs and adult females were harvested on nesting beaches. Juvenile and adults were harvested on feeding grounds. Although this practice is much less common now, it still occurs in many areas around the world.

Commercial Fishing. Accidental capture in fishing gear is a serious ongoing cause of death that also negatively affects most sea turtle populations.

Pollution:

Trash. Turtles eat a wide array of the 24,000 metric tons of floating trash dumped in the ocean each year. This includes such items as bags, sheets, pellets, balloons and abandoned fishing line. Sea turtles may mistake the floating plastic for jellyfish, a common food item. When turtles eat plastic, it causes many health concerns, including blocked intestines, malnutrition, suffocation, ulcers and starvation. Ingested plastics also release toxins that accumulate in the turtles tissues. These toxins lead to thinner eggshells, tissue damage and unusual behavior.

Artificial lighting. Artificial light impacts nesting females and hatchlings. Females seem to prefer nesting on beaches free of artificial lighting. Hatchlings automatically move towards the ocean using reflected moonlight or starlight on the water as a guide. Artificial light is brighter and can confuse them so they navigate towards that light and away from the ocean. Artificial lighting causes tens of thousands of hatchling deaths per year.

Climate Change. Changes in global temperatures can affect the turtles in many ways.

- Since the sex of sea turtle hatchlings depends on the temperature at which the eggs were incubated, high sand temperatures may change sex ratios resulting in too few males to keep the population going.

- As water levels rise, a number of good nesting beaches will be lost.

- The areas where sea turtles feed may be dramatically altered by climate change.

Click here for more information on the impact of climate change on sea turtle populations.

Habitat Destruction. Habitat destruction and intrusion on the habitat by humans is a serious threat to sea turtles worldwide. Beach development for people deprives the turtles of good nesting areas, forcing them to leave or nest closer to the water.

Growth of cities often leads to the siltation of sandy beaches and the construction of docks and marinas can destroy near-shore habitats. Boat traffic and dredging damages habitat and can also injure or kill turtles.

The flatback sea turtle is the least studied of the sea turtles. Our lack of knowledge about the population and their life history makes it very difficult to understand what this species needs to survive and thrive.

Conservation

Australia lists this species as Vulnerable as defined by the their Environment Protection & Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999). Internationally, the flatback sea turtle is listed as Data Deficient by the International Union for the Conseration of Nature (IUCN), indicating they do not have enough information to determine its vulnerability to extinction.

The government of Australia has put a number of conservation measures in place to protect all of the marine turtles of Australia. Much of the flatback sea turtle’s habitat is protected. Efforts to reduce bycatch by using Turtle Excluder Devices (TED) are required by law in the Northern Prawn Fishery.

Actions such as restricting boat speeds in areas of important marine turtle habitat, developing management plans for nesting beaches and a code of conduct for tour operators on beaches, as well as creating plans to ensure traditional indigenous harvests are undertaken in a sustainable manner have been put in place.

Australian Government. 2009. EPBC Act List of Threatened Fauna. Accessed March 30, 2012.

“Flatback Sea Turtles, Natator depressus ~ MarineBio.org.” MarineBio Conservation Society. Web. Thursday, July 31, 2014.

IUCN Marine Turtle Specialist Group. Flatback Turtle: Natator depressus. Accessed March 30, 2012.

Pendoley, K.L.; Bell, C.D.; McCracken, R.; Ball, K.R.; Sherborne, J.; Oates, J.E.; Becker, P.; Vitenbergs, A.; Whittock, P.A. (2014). “Reproductive biology of the flatback turtle Natator depressus in Western Australia.” Endangered Species Research 23: 115-123.

Sea Turtle Conservancy. Species Fact Sheet: Flatback Sea Turtle (Online). Accessed March 30, 2012.

Spotila, James R. (2004). Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press and Oakwood Arts. ISBN 0-8018-8007-6.

World Wildlife Fund. Flatback Turtle.